According to a familiar saying, before you construct a building, be sure to count the cost.

All of the elements that came together to make Superman IV seemed right. Christopher Reeve was back, the cast was in place, a solid story was in development, and for the first time things looked bright. So what happened next, and where did everything go wrong?

Because of numerous financial missteps, including several of Cannon Films’ releases failing both critically and commercially at the box office, and having too many irons in the proverbial fire at the same time, producers Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus were left with no choice but to cut the original $40 million budget assigned to Superman IV down to just $17 million. Many key areas of production, including the all-important visual effects, were hit by the reduced budget. It didn’t help matters that Cannon threw much of the budget for IV toward what they felt would be the bigger blockbuster, their film version of Masters of the Universe. Golan would later state that he would rather make twenty or thirty movies for a million dollars apiece than one movie for $20-30 million. Toward the end of 1986, Warner Bros. came in to alleviate some of the financial burdens carried by Cannon Films, but even that could not help the film. And Christopher Reeve was facing personal issues on the home front, which also affected his work on the film. Nonetheless, he remained committed to the film from start to finish. At one point it had been suggested during production that Reeve might portray the film’s secondary antagonist, the Nuclear Man, but that part went to novice actor Mark Pillow instead (with the character’s voice dubbed by Gene Hackman).

With the reduced budget, cast and crew shot the film in numerous locations in England, among them Milton Keynes (which doubled as Metropolis and the United Nations), Hertfordshire (which did a great job recreating the Kent farm and the Smallville cemetery), and at Elstree Studios throughout the fall and winter of 1986 and into January 1987. They could not afford to go on location for some key scenes in New York City, even though several spectacular shots of the city are featured throughout. Reeve would later state in his 1998 autobiography Still Me, “We were…hampered by budget constraints and cutbacks in all departments. Cannon Films had nearly thirty projects in the works at the time, and Superman IV received no special consideration. For example, (Lawrence) Konner and (Mark) Rosenthal wrote a scene in which Superman lands on 42nd Street and walks down the double yellow lines to the United Nations, where he gives a speech. If that had been a scene in Superman I, we would have actually shot it on 42nd Street. Dick Donner would have choreographed hundreds of pedestrians and vehicles and cut to people gawking out of office windows at the sight of Superman walking down the street like the Pied Piper. Instead we had to shoot at an industrial park in England in the rain with about a hundred extras, not a car in sight, and a dozen pigeons thrown in for atmosphere. Even if the story had been brilliant, I don’t think that we could ever have lived up to the audience’s expectations with this approach.”

It was around December 1986 that Christopher Reeve made his directorial debut, shooting the second-unit fight scenes between Superman and the second Nuclear Man on the moon. In a 2021 interview for the CapedWonder Superman Podcast, Mark Pillow recalled how Reeve took charge of the moon sequences. “He actually, as far as I can remember, he basically shot all of the moon sequences, so he covered everything. So he was very thorough, so we would shoot it multiple times, we’d change angles,…he was very much in charge. I think he felt pretty comfortable in that position. I can certainly have seen him, bless his heart, doing more directing later on. But yes, the moon sequence was, I believe, all him.”

Pillow also recalled the problems that occurred during filming, which included working on a lower budget, and the differences Reeve and Furie experienced. “They pretty much kept it to themselves. When I came to work, it was just to do the very best that I could that day, and I didn’t sense from Chris that I’m sure he was very upset and disappointed, I think. But it seems like I saw less of Sidney at a certain point, and it’s only putting two and two together later on thinking that possibly he was disappointed by the way things were going, but I didn’t have any sense of it myself while I was there.”

Once the film wrapped principal photography, the race was on to complete the film’s crucial special effects and flying sequences. According to Mark Rosenthal, much of the original special effects team that had been hired for the film was let go once the budget was cut. Instead of six months, Harrison Ellenshaw and his team had a mere thirty days to get it done. This explains why certain flying shots were repeated multiple times in the final film and its respective cut scenes.

Golan and Globus had also intended to bring back yet another key member of the original team: John Williams. While his schedule in composing the score to The Witches of Eastwick and conducting the Boston Pops proved to be a conflict with the film, he agreed to write three new themes for the supporting characters of Lacy Warfield, the Nuclear Man, and Jeremy, and turned to long time collaborator Alexander Courage of Star Trek fame to handle the final scoring duties. Even then the reduced budget affected the scoring process, with some cues very rarely getting a second take. Paul Fishman, son of Cannon music producer Jack Fishman, recorded several pieces of source music for the film, and Warner Bros. Records made plans for a soundtrack album similar to the Superman III LP a few years earlier, with the A side of the album comprised of cues from the orchestral score and the B side comprised of Paul Fishman’s source music and the Jerry Lee Lewis hit “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On” to underscore Lenny Luthor’s first appearance in the film.

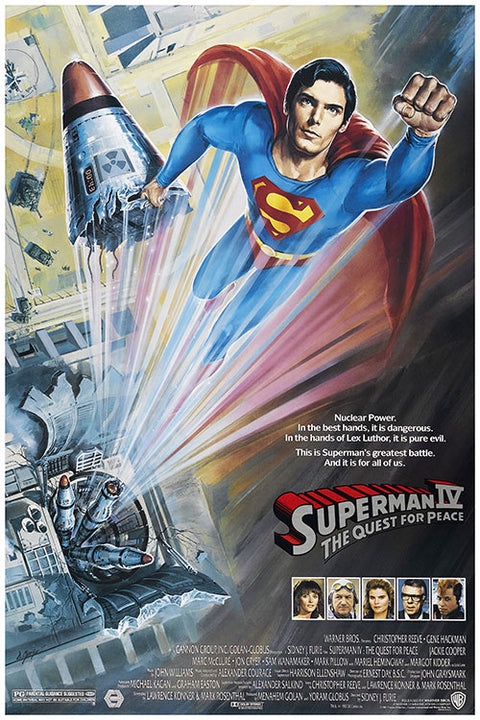

In the spring of 1987, Cannon Films released the first teaser trailer for Superman IV, and for all intents and purposes it felt like a big film indeed. They had crafted their trailer to echo the first teaser trailer from the first film, with sweeping cast credits and the original recording of John Williams’ main title theme to announce the film’s release that summer. Only one piece of footage was used in the spoiler-free trailer, of Superman flying in space from the climax of the film. Based on the teaser trailer alone, the film seemed to hold promise.

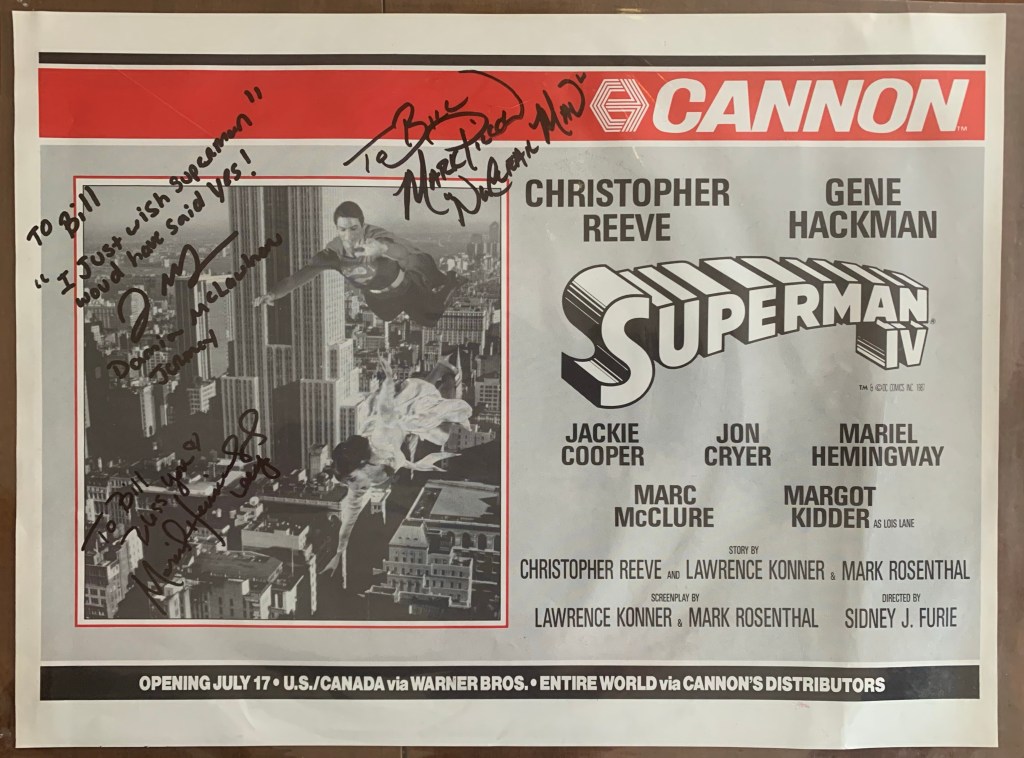

As late as the middle of May 1987, the film was still referred to simply as Superman IV, and it was set for release on July 17th that year in the United States and Canada through Warner Bros. and through the rest of the world from Cannon. It would be just a short time before the film’s release, possibly late May or early June, that the subtitle The Quest for Peace was added at Christopher Reeve’s request. Shortly afterwards, trailers and TV spots were prepared for domestic and international screenings, each one addressing key points of the film’s story. By that time the film’s release date was pushed back a week and rescheduled for July 24th.

Then, without the majority of us knowing, everything about the film fell apart, and what started out as Superman IV and what ended up as Superman IV: The Quest for Peace are two totally different things.

I went to the Metrocenter Cinema 4, where all of the previous Superman films had premiered, to see the new film on opening day, and I had my expectations about the film. I was all of twenty years old, two months out from my twenty-first birthday, and looking forward to my fourth year at Mississippi College. As opposed to having my parents with me, who went with me to see the first three films, I went by myself. Looking back, I should have realized that something was wrong.

The local newspaper advertised five screenings for the film, as opposed to the usual four. That meant that the film would run somewhere around 90 to 97 minutes. It was actually shorter than that, a mere 89 minutes in length. At the end of the film, I found myself thinking, “That’s it?” There had to have been more than this. After all, the interviews with Christopher Reeve on television and in the Starlog and Comics Scene magazines promised something special. But what struck me odd was that a group of boys, who had to have been no more than six or seven years old each, were more excited about the forthcoming release of Robocop, a film that had been toned down from its original X rating to an R because of the excessive violence. What had happened in the nine years since the release of the original Superman to jade young people’s perception of good and bad, right and wrong? Those thoughts stayed with me into the early 1990’s, as I pursued my master’s degree in English education.

And yet the clues were there. Scores of prominent visual effects were used multiple times throughout the film. Editing and pacing seemed choppy. The once convincing visual effects, which had earned the first film an Academy Award, looked second-rate at best. Nothing seemed to make sense. Logic seemed to be thrown out the window at times. The final film had all of the quality of a TV movie of the week.

At the time of the film’s release, Starlog ran a news blurb in one of its issues stating that 30 minutes of footage had been cut from Superman IV before its release. That meant that the film had to have been at least two hours long. But it was the critical interview with Sidney J. Furie that seemed to bury the film. Along with numerous photos of scenes that were not in the final film, Furie blatantly stated in no uncertain terms that he didn’t care whether or not the film succeeded or failed. In his interview for Starlog just before the film’s release, Furie stated, “What will it do for me? It won’t do s—-. If Superman IV is a hit, it won’t do s—-, and if it’s a failure, it couldn’t matter less to me because the people who know me, know me.”

In looking back on the film in 2006, Margot Kidder said, “You can’t make a good movie out of a bad script, and it simply didn’t work and fell flat on its face, but I thought its ambitions were good.” Kidder also commented in another interview that Reeve and Furie had different approaches to the film and frequently clashed.

Superman IV earned a mere $15.5 million in its U.S. release and another $21 million in its overseas releases, for an overall total of over $36.5 million, which was close to the initial budget for the film before the budget was cut in half, making it the only Superman film to fail at the box office both critically and commercially. In interviews conducted in 2006, Ilya Salkind stated, “I don’t know how to say this but, I mean, there was a Superman IV which did not help the cause of comic book movies…. I would say that if there’s one film that killed Superman at that point, it was Superman IV,” while Annette O’Toole curiously asked, “Was there a Superman IV? I didn’t even see that one.”

Mark Rosenthal also stated, “Cannon, at that time, had come out of this real, in the old days, the real low-budget movies…. And I think they were trying to buy legitimacy, you know, with this one big paycheck. I do know that cutting the special effects budget and the general budget of the movie, I think, came out of their financial shortcomings.”

Pierre Spengler echoed Rosenthal’s comments as well, adding, “They probably didn’t understand how big special effects films need to be made. When you make a big film like Superman, one of your stars is the special effect. It’s an expensive star. You cannot get away with being cheap on that.”

Rosenthal also discussed the failure of the Nuclear Man to connect with filmgoers. “I also think that the conception of Nuclear Man was also sort of dumbed down. We thought, why not conceive of Nuclear Man, which is cloned from (Superman), as some kind of dark shadow of his own? And we actually talked with Chris about playing both roles. It would have been a lot tougher and certainly more expensive to have Chris play both roles. But that’s what its original conception was.”

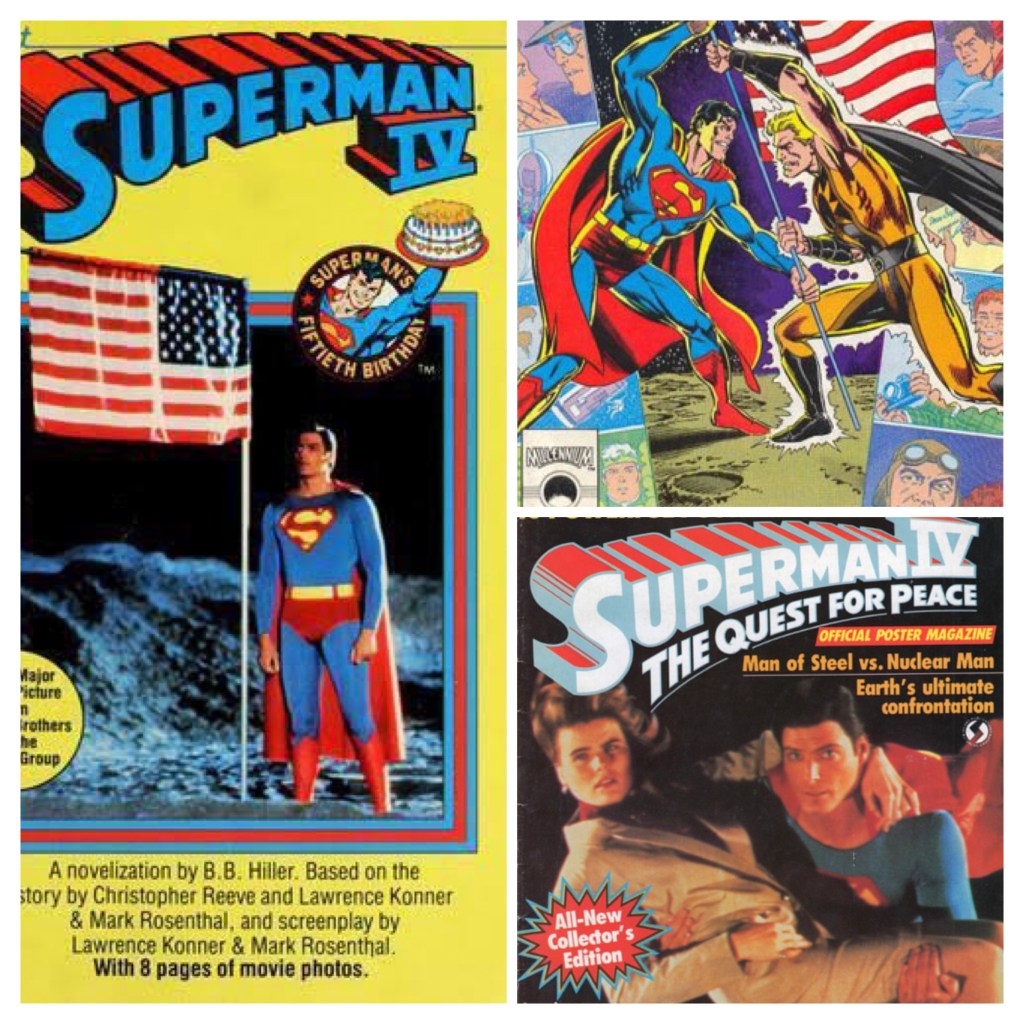

A number of the tie-ins were aborted as well. The planned soundtrack album was cancelled. Topps, who had handled the trading cards for the previous films, never released any cards for the new film. Scholastic Books produced three paperback books obviously geared toward juvenile audiences. DC Comics produced an illustrated adaptation that, while it filled in some of the gaps in the story, seemed lackluster and uninspiring. The Starlog Press poster magazine fared no better. In a 1993 interview with Wizard Press for a special publication devoted to Superman, Marc McClure offered his thoughts on the film’s failure. “The ending was moved to the middle, and comprehension was lost by anyone beyond the age of three.”

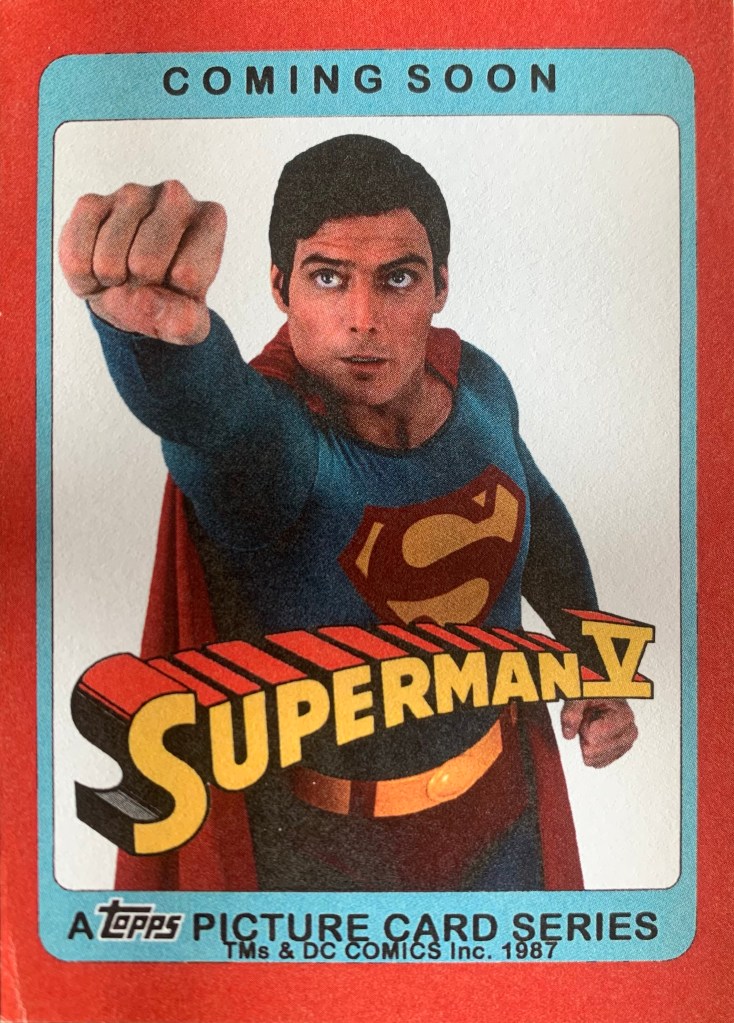

Despite its failure, that fall Golan and Globus announced that pre-production had begun on Superman V, which was scheduled for release in the summer of 1989. I remember reading that they were considering using a portion of the cut footage from IV for the new film, that Albert Pyun had been announced to direct the next installment, and that it was possible that Christopher Reeve might be replaced. Even into the first part of 1988, Cannon was sincere in its intentions about a fifth film, and it was announced at Cannes along with a slate of other projects in order to obtain funding for production. Ultimately, the rights to the Superman franchise returned to the Salkinds, which would, by the fall of 1993, be bought out in turn by Warner Bros. to handle all future film and television productions.

By this time the film’s two major creative forces seemed to distance themselves from the film. Sidney Furie remained indifferent about the film, refusing to discuss it for years afterwards. I had attempted to contact him via his agent in 1998, hoping to learn more about his work on the film. I never heard back from him. “I don’t want this to become an exercise in bashing Sidney Furie,” Mark Rosenthal said in the DVD audio commentary. “He certainly had his hands tied behind his back by the terrible cuts in budget in pre-production.”

Christopher Reeve was sadly affected by the entire project as well. The rushed quality of the film, coupled with his personal problems during filming and a plagiarism lawsuit in the aftermath of its release, all contributed to him closing the door on the project in later years. When he was offered the possibility of returning for a fifth installment in the early 1990’s, he felt that unless the film was a vast improvement upon IV and returned to the quality of what Richard Donner had brought to I and II, he would not consider it. This is why, in his 1998 book Still Me, he makes a statement that is short and to the point: “The less said about Superman IV, the better.” He had borne the brunt of the criticism about the film’s failure, and he had endured a difficult time in his life that he wanted to put behind him.

Rosenthal added in the DVD commentary, “The movie for everyone became an emblem of greed and chaos on the part of people who were in over their heads, an unfortunate and almost unethical betrayal of Chris Reeve, who really single-handedly brought Superman IV together.”

I remember the day after Christopher Reeve passed away in 2004, Jim Bowers and I exchanged our thoughts about Chris. He related to me how he had once offered Chris a copy of the extended version of IV, which Chris politely declined. Even in the later years toward the end of his life, Reeve wanted nothing to do with Superman IV anymore, and we can’t blame him for that.

But even then there lay a mystery, one which I was determined to solve. What happened to the missing footage to Superman IV? Next time I will discuss my attempts to solve the mystery, one which has eluded fans for years.

(Some screenshots and photographs from Superman IV in this blog are courtesy of CapedWonder.com.)